Joe Andoe Rides Again

by Deborah Solomon

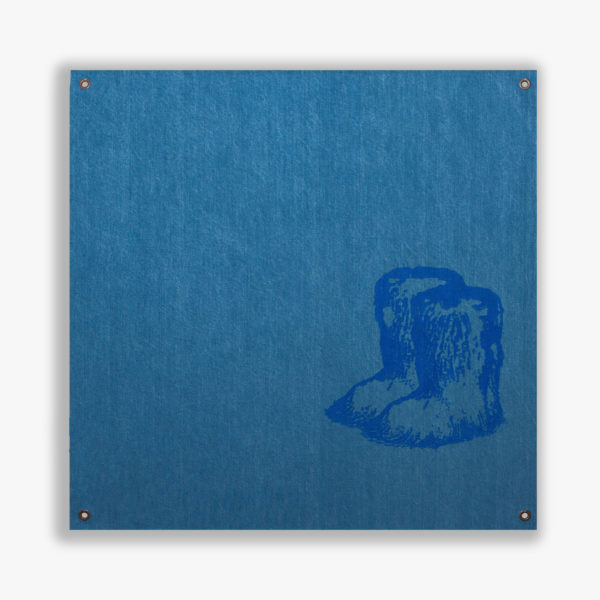

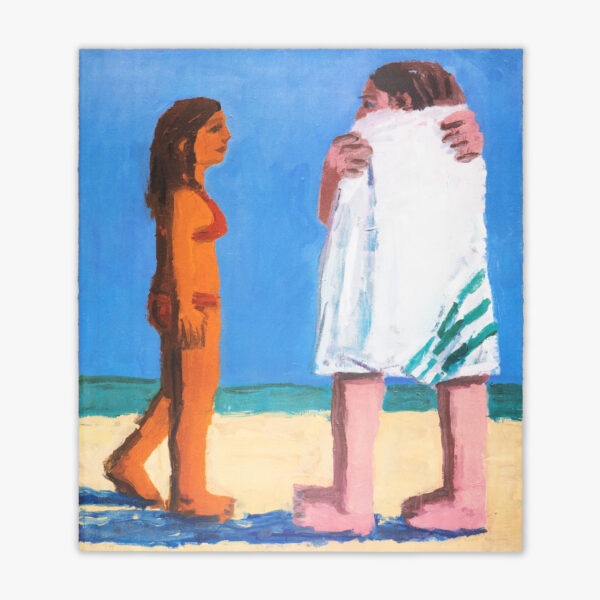

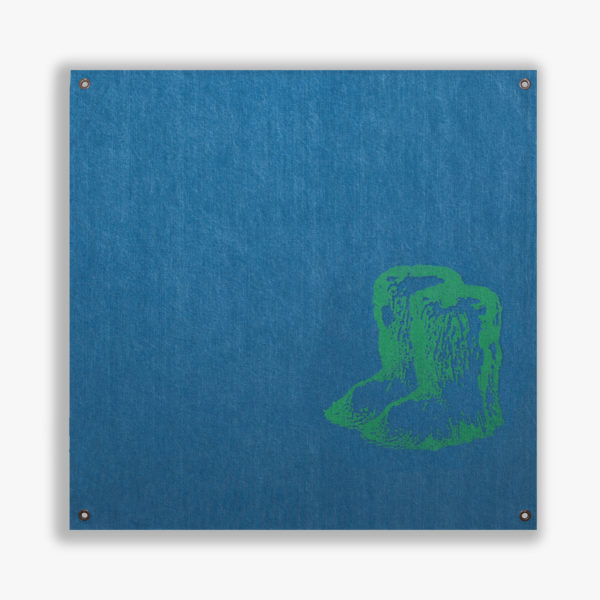

It has now been almost 40 years since Joe Andoe headed east, arriving in New York from his native Tulsa, Oklahoma. He soon won attention for lean, roughly poetic paintings of horses and winding roads. For starters, he’s an important forerunner of the photo-based realism that has become the default style among younger artists today. Moreover, his work can be read as a form of social critique, with its views of a robust America on the brink of disappearance. Andoe usually works in monochrome – especially ivory black or mars black — and many of his paintings have the somber tonality of vintage photographs. When he paints a picture of a horse – or for that matter, of quadrupeds including wolves, dogs and buffalos — he isn’t working from life. Rather, he favors photographs, which these days he finds online, prints out, and transfers freehand onto canvas. His use of found photographs allows him to operate at an obvious distance from his subjects, and leaves his work unencumbered by a suggestion of nature worship or other forms of transcendence.

His painting technique is almost comically casual. Using his hands, or paper towels, he starts with a pigment-covered canvas and wipes paint off of his surface, bringing images out of darkness. Some of his scenes can remind you of Vija Celmins’s nighttime skies, except they’re much greasier. It is probably relevant that “oil,” for Andoe, describes not only his preferred painting substance but the sought- after prize of countless prayers in his home state. Andoe, who is now 63, grew up in Tulsa and received an M.F.A. from the University of Oklahoma. In 1982, the year after he graduated, he moved to New York, which continues to be his home. He is part of the generation that came of age after the dominance of Minimalism, which, as everyone knows, fetishized geometric forms and sleek surfaces and practically outlawed the sensual medium of oil-on-canvas. Andoe, officially, is a post-Minimalist whose work can at times resemble that of the New Image painters (such as Susan Rothenberg and Robert Moskowitz) who emerged in the ‘70s and returned figuration to painting.

Put another way, you might say that Andoe has fused post-modern figurative painting with views rooted in the Old West. His works can evoke the days when cowboys and their loyal horses flashed across the big screen at the drive-in, and the world was still black and white. Andoe is not an ironic artist, and he isn’t satirizing the old days. To the contrary, he can’t stop thinking about them. The strong male faces of wolves and horses that gaze directly at him as he coaxes them to life on canvas are both here and not here. That is where the poignancy resides in his work, in his pursuit of an absence.